The Wreck of "The Marquam Grand"

The Marquam: Portland’s first sky scraper:

It was the city’s first modern office building and an extravagant, luxurious theater.

It towered above Morrison Street, between 6th and 7th (renamed Broadway in 1913), in the new center of the city, across from the regal Hotel Portland.

It was opulent, exclusive, electric-powered and fully fire-proof.

It was also collapsible.

The Marquam was built in 1891 by Phillip A. Marquam, retired judge and real estate investor (Marquam Hill etc...) on land (Block #178) that he acquired from William W. Chapman in 1852 in lieu of payment for a five hundred dollar legal bill.

“When he had shown me around the town he said he would take me out a ways and show me a block he had taken on payment of a legal bill amounting to $500.00. We walked through a cow pasture, climbed over a rail fence and clambered over fallen logs and through the heavy brush to his block of land. It had a heavy stand of trees on it –some four or five feet thick.

He told me he was going to have the wood cut and sold for cordwood, though he doubted there was enough wood on it equal to the amount of the bill he had taken it for.

He said that while it was pretty far out, in time the land would be some value as a building site.”

-Dr J. A. Cardwell to Fred Lockley in the Oregon Sunday Journal, February 22 1914.

By 1889, Portland’s downtown had shifted inland in the years of growth that followed the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1883. Phillip Marquam’s block, once on the outskirts of town, was prime urban real-estate.

Marquam began work on the building that would bear his name, a combination high-rise office structure and a first-class theater: The Marquam Grand Opera House.

The complex was essentially a T in shape, with a ten story office building which faced Morrison, and a five story high theater that reached back to Alder Street. The entrance to the theater was on Morrison, with side entrances on 6th and 7th.

The building was heated with steam and powered by electricity. It was considered fire-proof, constructed with eight solid walls running north to south that divided the building into nine separate compartments, which were linked by hallways on the lower eight floors.

It was expensive to build.

The vast amount of bricks required for the building enticed local brick yards to form a combine to raise their prices. Marquam was forced to form his own brick yard, and eventually, to import bricks from San Francisco. Years later, the quality of those bricks would be an issue of debate.

The theater that got all the attention...

Seating 1,600, built for the “carriage trade,” the Marquam Grand was an “outpost of sophistication in the far west.”

After the opening performance, of “Faust,” its star, the diva Emma Juch, pronounced it: “The equal of any theatres visited in this country and in Europe”.

The Marquam Grand Opera House

The Handsomest Most Complete and Only Absolutely Fire-proof Theatre in the Pacific Northwest

Playing High Class Attractions Only

-Advertisement in the 1893 Portland City Directory.

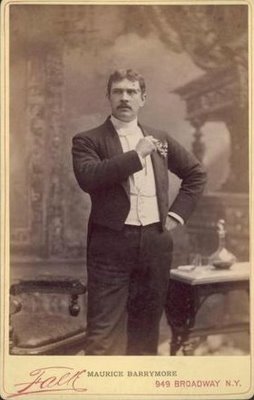

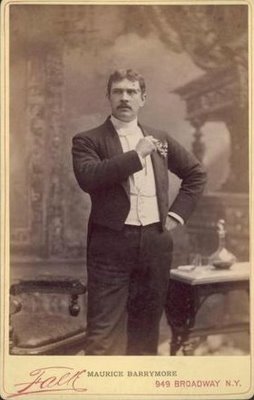

Maurice Barrymore circa 1891.

Maurice Barrymore, father of John, Ethel and Lionel, great grandfather of Drew, starred at the Marquam Grand in productions such as “Aristocracy,” “Shenandoah” and "Alabama".

When Sandra Bernhardt performed there in 1891, tickets to the show had to be auctioned off due to their high demand.

George Baker, later the beloved, (but sometimes not so loveable) Mayor of Portland (from 1917 to 1933) started his theatric carrier there as an electrician. Eventually he would manage the theater.

Mark Twain entertained a standing room only audience at the Marquam Grand on August 9th 1895.

World Famous Lecturer Mark Twain:

Author of Innocents Abroad, Roughing It, The Gilded Age, Sketches, Tom Sawer, Pudden’head Wilson.

Prices for seats:

Lower floor: $1.00

Boxes: $7.50

Dress Circle .50 and .75

Gallery .25

-Advertisement for the Marquam Grand, Friday August 9th 1895.

“That the people of this city fully appreciate that this will be their last opportunity for hearing the most famous of all humorists, “Mark Twain,” is evidenced by the unusually large advance sale of seats for this evening at the Marquam Grand….”

-The Portland Dailey Telegram, Friday August 9th 1895.

Seventy-six years before Powell’s Books, Portland could sell-out an author event.

By 1904 it was advertised as the Marquam Grand Theatre, or simply, the Marquam Grand.

Due to the costs of financing his endeavor, Phillip A. Marquam lost his ownership in the building through foreclosure, although the Marquam Trust Company (Marquam’s real estate interests) continued to occupy part of the building. In 1908 the theater was re-opened as the Orpheum.

All was quiet in the city’s center in the pre-dawn hours of November 21st 1912.

Most of the guests at the Hotel Portland were asleep. Save for the occasional streetcar in all night (!)“Owl” service on Morrison, the streets were largely empty.

On the fourth floor of the Marquam Building, Eva Aldrich, a telephone operator for the Equitable Hospital Association, was working a graveyard shift. She was the only person in the north east portion of the building, which had been largely vacated due to a renovation project to replace the solid stone walls on the first floor with steel beams.

Suddenly, at around 4:00am, there was a quaking rumble and crash, as the outer wall of the building on the east side gave way and a segment of the three floors below where Aldrich worked collapsed on to 6th street.

With considerable aplomb, Eva Aldrich phoned the officers of the Equitable Hospital Association and informed them of what happened. Then she left the building.

Outside, she joined a growing crowd transfixed by the gouge in the side of the building. One did not have to be an engineer to guess what was likely to happen next.

By nine in the morning the crowd had grown into the thousands. From the grounds of the Pioneer Post Office, (the once and future Pioneer Courthouse) they stared up at the Marquam’s stricken unsupported upper floors. Movie crews and news photographers set up while the police worked to keep back the crowd.

Then, at 11:00 am, with a spectacular cascade of brick, the upper floors collapsed, as the cameras rolled. When the dust cleared it was apparent that an entire segment of the building had been turned to rubble, spilling across 6th against the Stearns Building on the north east corner of 6th and Morrison (today the location of the Meier and Frank building).

In the days that followed, it was announced that the Marquam would be rebuilt.

Further inspection by the city however, indicated that the west tower of the building was also in danger of collapse.

Mayor Rushlight ordered Morrison closed, which forced the detour of numerous streetcar lines, as well as 6th street between Morrison and Alder.

Sound Construction and Engineering Company, which had been working on the Marquam’s renovation, blamed the collapse on shoddy construction and materials, a charge angrily denied by the Marquam family (Phillip A. Marquam had died earlier in the year).

Later in the week the decision was made to demolish the office building portion of the Marquam complex.

The Orpheum Theater, although structural separate from damaged part of the building, was ordered to remain closed indefinitely. The Orpheum re-opened at a temporary location in the nearby Bungalow Theater. It was the first in a series of moves for the Orpheum, which lead to its location of many years at the present site of Nordstrom’s

The view north, 6th Street from Morrison circa 1910-1912. The Stearns building, which was damaged by the Marquam’s debris, is to the far right. Note the advertisement for the Orpheum Theater, a block away, above 6th and Alder.

It took just sixty days to fully demolish the Marquam Building.

Sound Construction and Engineering proudly noted that there were no accidents or deaths during the demolition.

“Great care was taken to make all scaffolds and supports solid before employees were allowed to go on them…”

-The Portland Evening Telegram, January 4th 1913.

In 1914 the Northwest Bank Building (now known as the American Bank Building) was completed on the site of the Marquam.

The former opera house was re-opened as the Baker Theater. It was ran by the George Baker, (later Mayor of Portland). Access was from Broadway and 6th by alleys that ran behind the Northwest Bank Building. It was torn down in 1922.

The Selling Building was built two years before the collapse in 1910, in the pocket created by the Marquam and its theater (the Orepheum, which can be seen at the far right). The Selling still exists today (#610 Alder Street).

Today the American Bank Building, bordering on Pioneer Courthouse Square, sits on the site of the Marquam.

The new downtown of Portland of the 1890s was a tough room to play in. Of the three monumental edifices shown: the Hotel Portland, the Marquam and the Oregonian Building, none survive. The neighboring Pioneer Courthouse (and post office) built in 1875 in what was then edge of town, witnessed the rise and fall of all three buildings.

Arcades Postscript:

In the post "Hung Over on Burnside" about the “arcaded” buildings of Portland, I had hoped to include a picture of one of them prior to being “arcaded.” None were available. Recently I discovered one in an old photo book called “Portland” published by G.K. Gill around 1910.

Below is a picture of the Burkhard Building, before Burnside was widened. It can also be seen in the post, years later, with the sidewalk running through the front of its first floor.

Off Line Too Soon: Portland's Electric Buses

Portland once had an electric bus network that was state-of-the-art modern, clean, inexpensive and popular. Like a streetcar they drew power from electric catenary suspended from poles. Like conventional buses they rode on rubber tires. This allowed curbside loading which was not possible for streetcars whose tracks were laid in the center of the road.

Portland once had an electric bus network that was state-of-the-art modern, clean, inexpensive and popular. Like a streetcar they drew power from electric catenary suspended from poles. Like conventional buses they rode on rubber tires. This allowed curbside loading which was not possible for streetcars whose tracks were laid in the center of the road.

Widely known as trackless trolleys or trolley buses, in Portland they were called trolley coaches.

They were never the predominate mode of public transportation in the city.

Prior to World War II they supplemented a decaying streetcar system. After the war they were gradually replaced by ever increasing orders of motor buses. If the war had not interrupted their progress, it is possible that they would still be running in Portland as they continue to do in Vancouver BC, Seattle and San Francisco.

They were quiet, economical and clean. They had zero greenhouse gas emissions.

In Portland they are largely forgotten.

The 1930s were hard times for public transportation in Portland.

The streetcar lines of the once mighty Portland Railway Light and Power Company were re-organized as a separate susidiary called Portland Traction to put financial distance between the streetcar system and its profitable electric utility company parents.

Ridership was down but fares were prohibited to rise by terms of the company's operating franchise. The vast majority of its equipment pre-dated World War I and its infrastructure was becoming ever more expensive to repair. At one point the company offered the city its entire track network to be used and maintained as a public throughfare (like roads or bridges) for the cost of one dollar (Portland Traction would have continued to provide service on the city's tracks).

The city demurred.

To make matters worse, just when the franchise which allowed the company to operate on city streets was due to expire, and an unexpected rival appeared on the scene. The Portland Motor Coach Company, a front for the United Cities Motor Transport , a subsidiary of bus manufactorer Yellow Coach (later a part of General Motors) offered to operate a motor bus system in Portland in the place of the electric utility owned streetcar system.

Portland Traction's response to the threat was to explore the use of trolley buses which were gaining popularity in other cities.

A plan was submitted to the city council for "coordinated service" which utilized new trolley coaches, modern streetcars, and motor buses for the outer routes.

A trolley coach test loop was then set up on Broadway, Jefferson, 13th and Yamhill using coaches borrowed from Toledo Ohio's Community Traction Company.

Responses listed in a "Coodinated Service" pamphlet "from 10,000 opinions" included:

"More comfortable..safer..good looking." -A.N.

"Amazing flexibility in traffic." -M.F.N.

"So much better in every way." -E.M.

"Less noise, no fumes, more speed." -M.L.M.

"Uses electricity, a home product." -E.W.N.

It is possible that the quotes were creations of Portland Traction's publicity department but none the less, public acceptance was enthusiatic and fast in coming.

The Yellow Coach offer of a motor coach bus system was withdrawn.

On January 31 1936, in the midst of the public excitement over the new trolley coaches, a new twenty year franchise was granted to Portland Traction. A modernization plan was adopted which called for the current system of 27 streetcar lines and 7 motor coach lines to be upgraded into system with 7 trolley coach lines (45 miles), 14 streetcar lines (63 miles) and 9 motor coach lines (47 miles).

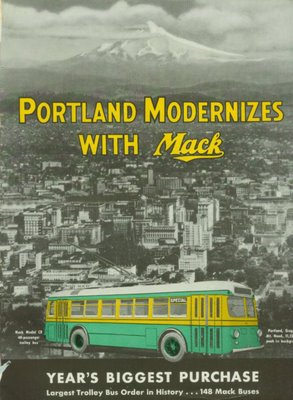

A new green and yellow-cream paint scheme, selected by the school children of Portland, was adopted by the company for its trolley coaches, streetcars and buses.

One of the borrowed Toledo trolley coaches loading on Broadway and Yamhill on the test loop. The Hotel Portland (now the location of Pioneer Courthouse Square) is in the background.

"Coodinated Transportation Service" was touted in this brochure given out at the test loop of the trolley coach. The streetcars featured were the 15 modern "Broadway" cars delivered in 1932.

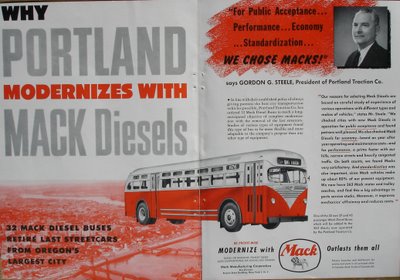

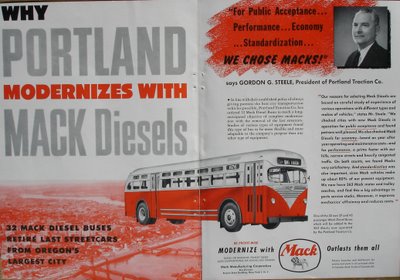

"Portland Modernizes with Mack" is proclaimed by an advertisement for the Mack CR 40-passenger trolley bus.

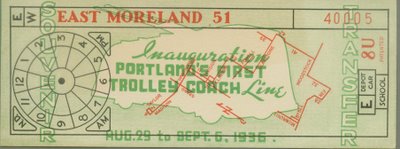

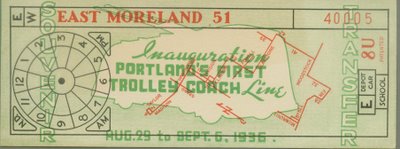

The Eastmoreland line was the first trolley coach route to be inaugurated on August 29th 1936, followed by the Hawthorne (1936), Foster (1936), Sandy Blvd (1936), 3rd Avenue (1937), St Johns (1937), Williams (1937), Interstate Avenue (1940), and Sellwood (1940).

A souvenir transfer celebrating the inauguration of Portland's fist trolley coach route, the Eastmoreland, August 29th through September 6th 1936. On the back it reads "Keep this transfer as a souvenir of a modernization program giving Portland one of the finest mass transportation systems in the world. You will value its possession in years to come." Portland Traction #318 in the maroon and cream paint scheme introduced in 1939.

Portland Traction #318 in the maroon and cream paint scheme introduced in 1939.

They were popular.

In a poll published by the Oregonian on April 9th 1940 on transit preferences, 80% of Portlanders favored the trolley coaches, 9% streetcars 2% gas buses, 1% "the present combination" while 8% "Don't Know."

The streetcars supporters were noted as being mostly over 50 years old. A middle aged widow noted that she liked "the old conductors." Several people mentioned they disliked the odor of the gasoline busses. Of the few people who did like gasoline busses, it was noted that all of them owned their own cars.

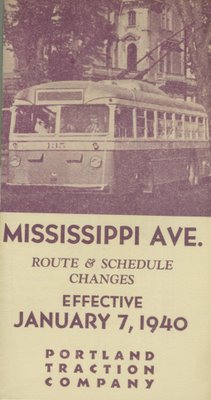

Portland Traction featured trolley coaches on all of there 1940 schedules including this one for the Missippi Avenue, a motor coach line in 1940. It would not be converted to trolley coach opeation until 1949.

Word War Two stalled the expansion of the trolley coach network.

The war placed a tremendous strain on the public transportation system.

In 1945 alone, Portland Traction hauled 163 million passengers, placing Portland in third place among American cities for that year. At the end of the war it was considered parmount to replace the streetcar system which was viewed by general public as decrepit.

Trolley coaches were not avaible for immediate post war production which left gasoline or diesel buses as the only option.

Support for the trolley coaches was so strong however, that in a poll done by the Oregonian of transit riders, ten to one favored trolley coaches, even if it meant waiting an additional three years for new equipment.

Commissioner Kenneth L. Cooper took a stand in favor of trolley coaches in a response to a protest by Lawrence and Grace Meissner against the company purchasing "new stink buses."

In 1946, the Portland Traction Company was sold to San Fransico based holding company named Portland Transit, which would operate Portland Traction (and its successor Rose City Transit) until the formation of Tri-Met in 1969.

"We will keep our present trackless trolleys: we like them and the people like them: but we will not have the finances at this time to put in the overhead systems for additional ones"

-Gordon Steele, President of the Portland Traction Company in the Oregonian, March 28 1946.

..."The Company believes that modern buses will be as popular as trackless trolleys. We doubt it".. The Oregonian May 8th 1946.

City Commissioner (later Mayor) Dorothy McCollough Lee released a report on July 13, 1946 which recommended trolley coach replacement for the Mt. Tabor, 23rd Avenue, Montavilla, Broadway, Willamette Heights, Alberta, Council Crest and Bridge Transfer streetcar lines.

In each case, over the next four years as the last streetcars were discontinued, buses were used as replacements.

An article about a new order of buses that appeared in the August 22 1946 Oregonian promised that gasoline odors would be eliminated by an "automatic de-gassing device." (!)

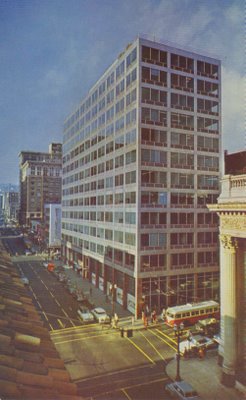

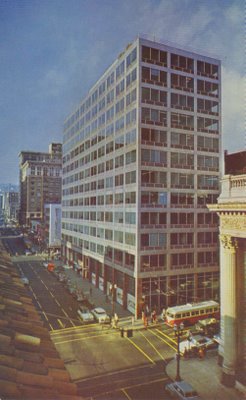

Portland Mid-Century Modern: The Equitable Building (today the Commonwealth Building) designed by Pietro Belluschi, and a trolley coach.

The postwar expansion of the trolley coach network finally resumed in 1949 with the addition of the Mississippi Line and an extension of Williams Avenue line in North Portland.

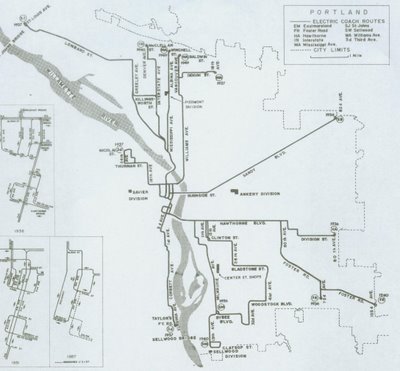

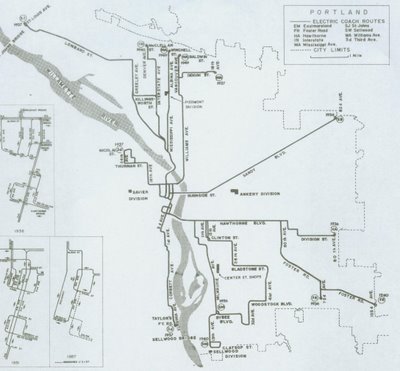

At the systems height circa 1949-1952 there were ten electric coach lines: St Johns, Interstate, Mississippi, Williams, Sandy Blvd, Hawthorne, Foster, Eastmoreland, Sellwood and 3rd Avenue.

Nine years after the last route was added, the entire network was gone.

(click on map to expand..)

Portland's Trolley Coach system at its height circa 1950. From Motor Coach Age, September 1971.

Portland was still "Modernizing with Mack," in this February 1950 advertisement, however with diesel buses which were credited with the removal of the final streetcar lines.

At transit ridership declined in the 1950s, Portland Traction moved away from electric powered transit, citing cost and technological improvements of the new diesel buses. According to figures provided by the company in 1951, it cost 43 cents a mile to operate a trolley coach, opposed to 38 cents a mile with a gas bus and 34 cents a mile with the new diesels. Maintenance of the overhead wire system was factored into the calculation.

If the war had not interrupted the expansion of the trolley coach lines, or, if Dorothy McCollough Lee's 1946 recommendations been followed, it would have been impractical to consider replacing the trolley coach network. As it was, the replacement of the final streetcar lines with motor coaches placed the tipping point clearly in the buses favor.

By November 21 1950 weekend service on all routes was covered by motor coaches. The Williams Avenue line was converted wholley to bus operation on February 17th 1952 and the 3rd Avenue line on August 10th 1953. Plummiting transit use allowed the conversions to take place with no additional equipment purchases.

In July 1953 Portland State student Donald K. Simpson lead an effort to return trolley coach operation on Saturdays, noting that the city ordinance that allowed bus subtitution on Saturdays had expired. In an emergency session, the city council voted to extend permission to Portland Traction to continue bus substitution.

"Electric trolley coaches are out of the picture because they cost four cents a mile more to operate and are almost 20 years behind in some phases of design."

"...As long as there are automobiles there will be fumes."

-Gordon Steele, President of the Portland Traction Company to the Lions Club,

November 27th 1953.

In 1956 the franchise that allowed the Portland Traction Company to provide the cities public transportation expired. A new company called Rose City Transit was created (though still owned, like Portland Traction, by San Francisco based Portland Transit) and granted a twenty-five year franchise. In 1956, a project which added approach ramps to the Hawthorne Bridge removed the trolley coaches from the Sellwood, Eastmoreland, Hawthorne and Foster lines in Southeast Portland. It also severed the Oregon City and Bellrose passenger inturban rail service to downtown Portland, easing the way for their (illegal) shutdown in 1958. The sign on the trolley coach reads: "you don't have to park a bus."

In 1956, a project which added approach ramps to the Hawthorne Bridge removed the trolley coaches from the Sellwood, Eastmoreland, Hawthorne and Foster lines in Southeast Portland. It also severed the Oregon City and Bellrose passenger inturban rail service to downtown Portland, easing the way for their (illegal) shutdown in 1958. The sign on the trolley coach reads: "you don't have to park a bus."

Rose City Transit announced the cessation of electric coach operation on January 29, 1958.

It soon became aparent however that there was not enough buses to cover the routes. Trolley coaches returned to the St. Johns, Interstate and Mississippi lines on February 25, 1958. On October 23, 1958 the company was finally able to retire last trolley coaches and replaced them with surplus diesel and gas busses. The wires came down shortly after.

"A few weeks ago the Rose City Transit Company, without any warning to the City Council, which in theory has regulatory powers over it as a public utility operating under public permit, took the trolley coaches out of service and began dismantling the trolley wires. Since it is evident the company does not intend to replace them and the Council plans to offer no more than feeble protests, Portlanders have probably seen the last of the fast, clean, oderless trolley buses that served them so well for twenty years." -Albert McCready, Associate Editor, the Oregonian, November 9th 1958.

Many of the coaches were scrapped, although one was stored for many years at Rose City Transit's (later Tri-Met's) Center Street Garage. One is rumored to be in Northern California.

Forty-five coaches were purchased by automobile dealer Joe Fisher, to be converted into portable cottages. The first was diplayed at the Fisher's lot and Burnside, priced "well under $3,000." Ruth Fisher of Jim Fisher Volvo remembers that Joe Fisher had lots of energy for the project, but that he had bought "a ton of them." Around half were sold as cottages "so it was a half good idea." The others were probably cut up after being stored for a long time in a lot near Tualitan. It is not known if any of the "trolley homes" still exist.Afterword: In the mid-1970s, at the height of the energy crisis, there was an attempt at a revival. The Citizens for Immediate Adoption of Trolleybuses, headed by Ray Polani, a savings and loan executive, recommended that Tri-Met convert its close-in routes to trolley bus operation, using refurbished coaches from Chicago. There was even the possibility that funding from the U.S. Urban Mass Transit Administration for 100 new diesel buses would be delayed if a suit was brought by the CIAT. Nothing came of of the groups efforts. The trolley coach was largely forgotten as a transit option in Portland.

How would Portland's transit system look today if the trolley coaches survived? Public ownership would still have been inevitable. A rail component for longer distance high density transportation would also be very likely, as evidenced cities such as San Francisco (Muni lightrail), Vacouver BC (Skytrain) and most recently Seattle (lightrail), which kept their trolley buses.

If the trolley coach routes had been expanded, perhaps during the 1970's energy crisis, thoroughfares such as 23rd, 39th, Broadway, Burnside, Barbur and Division could have acquired electric buses.

Assuming the bus mall would have still have been built, it would be a much quieter, cleaner place.

The outer system would likely be diesel powered, due to the expense of installing and maintaining electric catenary. But if something along the lines of the dual mode trolley-diesel buses (used until recently on lines through Seattle's transit tunnel) or recent "Hybrid" diesel-electric bus technology were adapted for the outer routes, Portland would have been very close to having an all electric, very low emission emitting transit system.

Today It would be very popular.

San Francisco's Muni operates a fleet of trolley buses. On Market Street they share the road with Muni's historic F Line streetcar fleet (here a streamlined PCC car from the 1940s) and private automobiles. Beneath Market Street, Muni runs a light rail subway, and beneath that, BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) a high capacity regional commuter rail system. Unlike Portland's future Transit Mall upgrade, busses on Market Street load from the curve while rail loads from pedestrian islands in the middle of the busy street. San Francisco CA, Market and Powell, March 16, 2004.

The Seattle Region's King County Metro has a large trolley bus system in the city's core. Seattle Washington, April 14, 2005.

TriMet currently operates two diesel-electric "Hybrid" buses. Small diesel engines power an electric generator that charges a battery pack on the roof, which turns the wheels of the bus. They are regarded as an experiment on TriMet, but Seattle's King County Metro Transit has purchased 210 similar vehicles. While delivering significantly lower emissions than a standard bus, the Hybrids cost more and have not been able to deliver hoped for fuel savings.

There are still traces of the trolley coach network in Portland, including a group of fourteen poles along Larrabee between Broadway and Interstate Avenue north of Memorial Coliseum. Painted green or black, some are used as light poles. North Larrabee and Interstate, October 1, 2006. The green light post, left of center, once supported trollley coach catenary. This intersection is no stranger to electric powered transit. The Willamette Bridge Railway built Portland's first electric streetcar through there, at the boundary between the cities of East Portland and Albina, in 1889. The streetcar line was discontinued 1938. The St Johns trolley coach line was installed in 1937 (the Interstate and Mississippi Ave trolley coach lines would later share the routing). The trolley coaches were removed in 1958. Interstate Max opened in 2004.

North Larrabee and Interstate, October 1, 2006. The green light post, left of center, once supported trollley coach catenary. This intersection is no stranger to electric powered transit. The Willamette Bridge Railway built Portland's first electric streetcar through there, at the boundary between the cities of East Portland and Albina, in 1889. The streetcar line was discontinued 1938. The St Johns trolley coach line was installed in 1937 (the Interstate and Mississippi Ave trolley coach lines would later share the routing). The trolley coaches were removed in 1958. Interstate Max opened in 2004.

Thanks to:

Alan Eisenberg, who preaches the Gospel of the Trolley Coach.

Ken Lantz, Art Greisser, Roy Bonn, Mike Parker and Dick Thompson; the usual suspects when a mystery about Portland transportation history is discovered.

Ruth Fisher of Jim Fisher Volvo, who remembered the Trolley Homes.